Lesson 7: Strategic Interdependence and Game-Theoretic Models

Repression and Resistance

In early August of 1962 in the city of Greenwood, Mississippi, Sam Block, just 23-years-old at the time, lead the first protest action in what would grow into a year-long campaign of mass resistance to the white supremacist regime that had ruled the region – denying black persons economic mobility, excluding them from political power and withholding state protection of their persons and property – since the 1880s. Ostensibly, Block’s protest was narrowly focused on the issue of voter registration. He lead a handful of local residents to the County Courthouse, walked into the County Clerk’s Office, and asked that he and the others in his group be registered to vote. Block and his companions were black, and repression by the local white supremacist regime prevented voting by all but a handful of the area’s black residents.

No doubt, Block hoped that his protest would, in combination with additional protests by thousands of others in the coming year, somehow end the suppression of black voting in Mississippi. But to think of Block’s protest as targeted narrowly at black voting rights is to misunderstand Block’s goals and methods, along with the nature of the white supremacist regimes that ruled Mississippi and other southern states during those years.

To correctly understand the politics Block was practicing, start by considering a puzzle: At the time of Block’s protest, Mississippi state law did not explicitly prohibit black voting, and there were small numbers of black residents of Greenwood who were registered to vote and who regularly cast ballots in local and state elections. Those black residents, moreover, had been registered to vote in the very same County Clerk’s Office where Block’s protest took place. They had registered, moreover, by doing what Block and his companions did: They walked into the County Clerk’s Office and asked the staff on duty to be registered. Evidently, their requests to register had been granted. Yet Block expected (correctly) that he and his companions’ requests to register on that morning in August 1962 would be denied. Why? Why would Block’s and his companions’ requests to register be denied when other black persons’ requests had been granted? More importantly, if black persons were permitted to register and vote in Greenwood, what exactly were Block and his companions protesting? And what exactly were they trying to achieve that was not already possible?

To solve this puzzle, there is one more fact you need to know about how white supremacy functioned in Greenwood Mississippi, and elsewhere in the “Deep South” region during the “Jim Crow” era that lasted from the end of the U.S. Civil War through sometime (depending on the place) in the late 1960s or early 1970s. The norms that southern white supremacists constructed and maintained in order to enforce racial hierarchy in the South concerned how black persons behaved in interpersonal interactions with white persons. Specifically, white supremacists demanded that black persons act with deference to white persons at all times and places. Black persons were expected to display deference through certain mannerisms (such as addressing white men and boys as “sir” and white women and girls as “ma’am”), and were expected to enact deference by obeying any command a white person should give them. Thus occasional instances in which powerful white persons granted “privileges” (such as a voter registration) to one or a few black persons were perfectly consistent with white supremacy. What the norms of southern white supremacy in fact prohibited was a black persons ever asserting or insisting on having, holding or gaining anything in any interaction with a white person.

Black dispossession and disenfranchisement in all domains, voting rights being just one, emerged from the enforcement of black deference. White supremacists norms of black deference were enforced through physical violence, organized and executed by police and white terrorist organizations, and through economic coercion organized and executed by economically powerful whites, such as farm owners and landlords. A black person who spoke assertively to a white person or who defied any demand any white person might make (especially if such assertion or refusal was done in public) put himself at risk of violent reprisal. If word of the black person’s failure to show deference was passed to the area’s enforcers of white supremacy, the “offender” might be evicted from their home, fired from their job and blacklisted by employers, imprisoned by police, beaten or murdered by white terrorists or lynched by a mob.

As long as white elites were perceived to be able to effectively and brutally punish black persons for failures to defer, any black person risked life and limb by asserting any want or need in any interaction with a white person. Thus, as of the early 1960s in places like the city of Greenwood, Mississippi, where white elites had been especially brutal and effective in enforcing norms of deference since the 1880s, blacks regularly deferred to whites in all economic and political transactions. This suppressed black wages, undermined black property rights, eliminated black political power and chronically undermined black persons’ bodily safety and material security.

So, when Sam Block and his companions walked into the County Clerk’s Office in Greenwood Mississippi in August of 1962, black voter registration was not their real concern. They aimed to inspire mass resistance to the rule of black deference in all contexts, only one of which was voter registration. Further, merely requesting to register to vote was not Block’s primary tactic. Block’s appearance at the courthouse was a protest only because of the manners he used in interacting with courthouse staff. Block’s specific aim at the Clerk’s Office that morning was to publicly and blatantly violate the white supremacist demand of black deference. The staff in the Clerk’s office, like all government officials in Greenwood, were white. Thus by requesting to register, Block set up an interaction where he and his companions could make a public demand of a white person, using none of the mannerisms (such as calling the clerk “sir” or “ma’am”) meant to show deference. Block knew that his un-deferential manners would provoke a stern refusal from the clerk, and likely an order to leave the courthouse. Block could then transgress further by talking back and ignoring the order to leave. For instance, in one of his early protest actions, after the clerk told him she wouldn’t give him and his companions registration papers to fill out, Block loudly demanded to know “what her job was anyway and why she couldn’t register them and how many Negroes were registered to vote at her office anyway?” (Payne 2007, 150) Moreover, after being rebuffed and told to leave, Block returned to the courthouse day after day during the month of August and repeated the same assertiveness and defiance.

Picture Block returning day after day and mouthing off to the white clerks and armed police in the building. All of this defiance occurred in public. So the scene you should picture is one in which the Block’s refusals to scrape and bow to the clerks and police are being watched by dozens of persons who are in the courthouse on other business. Block’s performances, then, likely humiliated and enraged the clerks and police, and some of the white bystanders who watched them. If when picturing this scene, you don’t feel fear for Block and his companions, then you’re not understanding the nature of white supremacy in Mississippi in 1962. All who lived there had a clear understanding of the rules: Failures of deference by black persons could be punished violently, up to and including death by lynching. Block was deliberately inviting the regime’s enforcers to target him.

Why did Block deliberately make himself a target of violence? What was he thinking? His protests put not only his own body and life at risk. They risked inviting a response that might deepen the white supremacists regime’s control of the black population. Had Block, for instance, been murdered or lynched shortly after his first few provocations, his protests might have reinforced fear of the regime among Greenwood’s black residents, thus worsening their subordination.1

In this lesson, you’ll think through Sam Block’s tactics and similar tactics used by political actors who aim to overthrow regimes that rule through repressive violence and coercion. By doing so, you’ll learn a concept that is central to understanding political behavior in general and political conflict especially: strategic interdependence. To depict political interactions that entail strategic interdependence, PPT uses a category of models called game-theoretic models. Thus in this lesson you’ll learn how to analyze and interpret the simplest kind of game-theoretic models, called simultaneous-move games.

How Repression Can Fail

Because repressive regimes can be so terrifyingly brutal, and because they can, through their repression, make any discontent in the populations they repress invisible to persons outside those populations, they can appear invincible. But in fact repressive regimes are regularly ousted from power. To understand Sam Block’s goals and tactics in Greenwood, it helps to be aware of two especially common pathways through which repressive regimes can fail.

Failure of Credibility

To say that repressive regimes rule through violence is only half-correct. It is true that these regimes, such as the regime that ruled Mississippi for most of the 20th century, the theocracy ruling present-day Iran, the Leninist regimes that ruled in the U.S.S.R. and Eastern Europe during the Cold War, and the Leninist regime that rules present-day China, regularly imprison, torture and execute persons who fail to comply with their views of acceptable speech, dress and other forms of expression. But there is a hard limit to what acts of violence by themselves can achieve.

Every repressive regime relies on organizations to carry out the acts of violence through which transgressions are punished. Typically, these organizations are some combination of state security forces (such as Mississippi’s local and state police) and non-state paramilitary or terrorist organizations acting in concert with the state (such as the Ku Klux Klan in Mississippi). Invariably, the security service personnel, the paramilitaries, and the regime-aligned terrorists are vastly outnumbered by the populations they police and terrorize.

So if enough persons in the repressed population transgress the regime’s demands all at once, there simply won’t be enough hands to punish them all. Thus repressive violence only works so long as most persons most of the time do not transgress the repressive regime’s rules. Historical accounts of life under repressive regimes suggest that when such widespread quiescence obtains, it does so because of widespread fear and expectations of punishment in the repressed population. When most persons in the repressed population believe that if they transgress the regime’s rules, they and possibly their loved ones will be brutally punished, most persons do not transgress the rules. Widespread fear of the regime keeps the number of persons transgressing its rules at any one time small enough for the security services, paramilitaries and terrorists to handle. Those few transgressors brutalized by the regime then become object lessons to everyone else, reinforcing widespread fear and quiescence.

All this means that a repressive regime can fail when its threats of violence cease to be credible to sufficiently large numbers of persons in the repressed population. If for whatever reason a large enough number of persons cease to fear the regime and all those person transgress the regime’s demands simultaneously (for instance, they engage in a massive street demonstration), their numbers can overwhelm the thugs who enforce the regime’s mandates. The result is that many of the transgressors go un-punished. Seeing many persons transgress the regime’s rules with impunity, additional persons in the repressed population may then cease to fear the regime. If these additional persons also transgress the regime’s rules then there will be even more examples of persons who transgressed without punishment. This undermines fear of the regime among even more persons, who may then also transgress the rules, and so on. This process can continue until there is no one left who sees the regime as a credible threat, and the widespread fear that the regime relied on for its power is gone.

Loss of Elite Support

Not all political elites in the societies ruled by repressive regimes are equally invested in the regime’s repressive program. In some regimes, repression is directed and enthusiastically supported only by a small faction of “conservative” or “hardline” elites, while other politically powerful factions tolerate the repression only so far as it does not threaten their status and prosperity. In such cases, the hardliners hold the power and resources they need to carry out repression only with the support and cooperation of other elite factions. Thus repression can fail when the “liberal” or “non-hardline” elites cease to support and cooperate with the hardliners.

For instance, after World War II, Mississippi began to industrialize. National firms began to locate manufacturing plants in the state, and a small but growing portion of its population began to work in fields of science and engineering. This lead to the emergence of a small but growing faction of the state’s white economic elite with close cultural and economic ties to white elites outside the deep South. Many members of this new segment of Mississippi’s elite tolerated, but were not enthusiastic about, the regime’s brutal subordination of black persons. Instances of nationally publicized extreme violence, such as lynchings, generated bad press for the state in the north, and that in turn threatened the new elite’s status within the national economic and cultural networks they had become a part of. Thus the new economic elite would support hardline white supremacists holding positions of power (such as county sheriff positions) only so long as regime violence was kept to a minimum.

There is a subtle detail about this example that is critical to understand for everything that follows in this lesson. Many of the members of Mississippi’s new economic elite did not object to the subordination of the state’s black population per se. What they found contrary to their interests and tastes were the acts of violence used to enforce that subordination. So, as long as white supremacist hardliners could maintain that subordination with minimal violence, members of the state’s new economic elite were willing to support hardliners’ holds on power. On the other hand, continuing to support hardliners’ holds on power would come at a cost for the new economic elite if hardliners could only maintain black subordination through frequent violence that ended up publicized in national media.

This means that there was a connection between widespread fear of police and white terrorist organizations among Mississippi’s black residents and support for Mississippi’s white supremacist regime from the state’s new economic elite. As long as the vast majority of black residents believed they would be brutally punished for any transgressions of white supremacists’ demands, transgressions of those demands would be relatively rare, and thus white supremacist violence used to punish those transgressions would be relatively rare as well. From the point of view of most members of the new economic elite, this would be perfectly acceptable. But if a substantial number of black residents ceased to fear the regime and began to transgress frequently and in large numbers, continued repression would require frequent and large scale violence. And that would diminish the status and risk the wealth of the new economic elite, making them less willing to support white supremacist hardliners’ hold on power.

Thus in the early 1960s, Mississippi’s white supremacist regime ruled very specifically through relatively low-profile violence (such as anonymous night time drive-by shootings) and threats of more spectacular violence that might make the national news. If activists like Sam Block could inspire black residents to transgress the regime’s demands frequently and in large numbers, the regime would be put in what, in retrospect, appears to have been an impossible position: By punishing transgressions with brutal violence, the regime might terrorize black residents and end the resistance, but only at the cost of losing support from the state’s new economic elite. On the other hand, by refraining from brutal violence, the regime might diminish the widespread fear of transgression among black residents, leading to a total collapse of the norm of black deference that was the foundation of black subordination.

Strategic Interdependence

Persons who organize and lead resistance campaigns against repressive regimes – such as Sam Block, the students who lead the 2019 pro-democracy demonstrations in Hong Kong, and the women organizing 2022’s street demonstrations against Iran’s theocracy – are extraordinary people. They are charismatic, physically courageous, and irrepressibly hopeful. But they are not superhuman. So they cannot know what their actions will lead to at the time they take them.

In retrospect, 60 years after the events of the early 1960s, we can see that Greenwood Mississippi’s white supremacist regime was fragile, and we can understand why Sam Block’s provocation and organizing, over the course of several months, inspired mass resistance to that brought down the regime. But in August 1962, Sam Block had no way of knowing for sure what his provocations in the courthouse would yield. He acted on the basis on conjectures and expectations about the effects of his actions, not knowledge.

So to understand Sam Block’s choices, along with the choices of police, white terrorists, white economic elites, and black residents that aggregated to the black resistance campaign and the un-doing of Greenwood’s thuggish regime, we cannot project our retrospective certainty onto the actors of the time. We must instead depict their uncertainty about the fruits of their actions, each of which, from their points of view might have lead to a variety of results.

In Lesson 4, you learned to depict uncertainty using probabilistic models. Probabilistic models are useful for modeling uncertainty in general, regardless of the causes of that uncertainty. But the politics of resistance and violent repression, and political conflict more generally, entail uncertainty that arises due to a very specific cause called strategic interdependence. Depicting the uncertainty faced by resistance leaders like Sam Block, and more generally the uncertainty actors face when they engage in political conflict, requires a clear understanding of how and why the uncertainty they face arises. So while probabilistic models are relevant and useful for modeling the uncertainties that arise in political conflict (and you will see them used in models in this and the next lesson), they are typically employed in models of political conflict only to supplement depictions of a more fundamental phenomenon: The strategic interdependence that causes uncertainty in the first place.

So what exactly is strategic interdependence?

Imagine an organizer who wishes to overthrow a repressive regime. Imagine this organizer is deciding whether or not to stage a protest that, if undertaken, he hopes will inspire mass resistance that could undermine the credibility of the regime’s threats of violence. Think, for instance, of Sam Block in July of 1962, when he was envisioning and planning the protests he eventually staged at the Greenwood courthouse in August.

Imagine the organizer thinks that if he stages a protest, the regime he hopes to bring down will respond in one of two ways. First, the regime might respond with overwhelming violence. Overwhelming violence would be brutal, spectacular and deeply traumatizing to those who witness and hear of it. If the organizer protests and the regime responds with overwhelming violence, the population the regime rules could end up even more frightened of the regime than it already is. Thus, suppose that if it provokes overwhelming violence, the effect of a protest will be the opposite of what the organizer hopes for. For instance, had Greenwood’s regime responded to Block’s August 1962 protests by successfully organizing a lynching, the mass resistance that Block hoped those protests would inspire would have become impossible.2

Alternatively, the regime might respond with limited violence. Limited violence would be harmful to its targets, but it might not be sufficiently disabling to prevent its targets from engaging in further resistance, or sufficiently terrifying to deter other persons joining the resistance. In fact, limited violence, if it is less brutal than what many persons in the repressed population expect from the regime, might cause persons to fear the regime less and thus weaken the credibility of the regime’s threats. Thus, suppose that if it provokes limited violence, the effect of the protest will be exactly what the organizer hopes for. In the event, for instance, limited violence is what Greenwood’s white supremacist regime visited on Sam Block in response to his August protests. A small gang of white terrorists rolled up on him in late August, dragged him into a field and beat him unconscious. This act of limited violence enabled Block to strengthen his campaign. The beating was widely heard about. And so by returning to the courthouse to protest again the day after the beating, Block convinced many of Greenwood’s black residents that he had the courage and toughness required to organize and lead successful mass resistance.

In this imaginary situation, the effect of the organizer’s actions on the outcomes the organizer cares about depend on the actions the regime takes in response. Thus the organizer’s preferences over his available actions (to protest or to not protest), depend on his expectations about how the regime will act. It looks like this:

| Organizer’s Expectations about Regime’s Response to Protest | Organizer’s Preferences |

|---|---|

| Overwhelming violence | Organizer prefers to not protest instead of protest |

| Limited violence | Organizer prefers to protest instead of not protest |

There are two key things to notice about the uncertainty the organizer faces in this situation. First, his uncertainty is about how other political actors (in this case, the thugs who carry out violence on behalf of the regime) will act. Second, which of the organizer’s actions is more compatible with his goals depends on how those other political actors will behave. This is an especially vexing form of uncertainty, since it makes neither of the organizer’s available actions clearly better for the organizer than the other. The most the organizer can know is which action is best for him if the regime’s thugs will respond in one way or another.

The organizer’s uncertainty about how the regime will respond if he stages a protest is an example of strategic dependence. The effect of the organizer’s action on the outcomes he cares about depend on the behavior of other actors. This dependence on the actions of others is strategic because the organizer’s expectations about the actions others will take affect his strategic considerations about which of his actions will better serve his goals. Thus his preferences over his actions depend on his expectations about how others will behave.

Strategic dependance becomes strategic interdependence only when two or more persons’ preferences over their available actions are mutually strategically dependent. So to illustrate strategic interdependence, we need to think about the organizer’s situation both from his point of view and from that of another political actor whose preferences over her available actions depend on whether or not the organizer protests.

Imagine the leader of the regime that the organizer hopes to overthrow. Suppose that, just like any leader of any repressive regime, this leader doesn’t actually carry out the acts of violence through which her regime rules. For that, she relies on a domestic security force and a regime-aligned terrorist group. Imagine that word has gotten around that the organizer is actively plotting her regime’s overthrow. Thus the leader’s chief of internal security has come to her asking for instructions: If the organizer stages a protest how do you want my men to respond? And what about our terrorist allies? If there is a protest, should I let them do their worst? Or should I start working now convince them that we will hang them out to dry if they start killing people? The leader of the regime, then, has two choices: She can order her chief to see to it that any protest by the organizer triggers overwhelming violence or, alternatively, she can order her security chief to put his dogs on a short leash, and see to it that any protest is met with only limited violence.

Suppose this leader holds power only through delicately balancing two opposed factions of elites: hardliners and liberals. For her, what is truly at stake in the order she gives to her security chief is the support her regime will enjoy from each faction. And how the order she gives affects the support her regime will get from each faction depends on whether or not the organizer mounts a protest. Thus she is strategically dependent on whether the organizer protests, just as the organizer is strategically dependent on whether she orders her thugs to respond to any protest with overwhelming violence or instead orders her thugs to respond to any protest with limited violence.

Specifically, suppose that if the organizer does protest, the leader thinks it will turn out better for her if she has ordered her security service to respond to any protest with limited violence. Limited violence in response to protest will strengthen her support from the liberal faction by demonstrating to them that she is not a blood thirsty maniac who will offend their sensibilities and force them to apologize for their government’s backwardness to their friends from elsewhere. On the other hand, suppose that if the organizer does not protest, the leader thinks it will turn out better for her if she has ordered her security service to respond to any protest with overwhelming violence. If the organizer does not protest, giving an order to respond to protest with overwhelming violence will have the benefit of reassuring the hardline faction of her zealous and ruthless commitment to their cause, yet, since no protest will occur, will not result in any actual public brutality that would alienate the liberal faction.

Thus the regime leader’s preference over her available actions depend on her expectations about the action the organizer will take as follows:

| Regime Leader’s Expectation about the Organizer’s Action | Regime Leaders’s Preferences |

|---|---|

| Will stage a protest | Leader prefers to order limited violence instead of overwhelming violence |

| Will not stage a protest | Leader prefers to order overwhelming violence instead of limited violence |

Together, the leader’s strategic dependence on the action chosen by the protest organizer, and the protest organizer’s strategic dependence on the action chosen by the regime leader amount to a situation of strategic interdependence. This is interdependence because it is a mutual condition between the resistance organizer and the regime leader. Each has two available actions: The resistance organizer can choose to protest or to not protest; The regime leader can choose to order limited violence in response to any protests or to order overwhelming violence in response to any protests. And each person’s preferences over their available actions depend on what action they expect their counterpart to take.

Before checking your understanding of strategic interdependence, there’s a subtle aspect of the concept that you should make sure to notice and comprehend: When two or more actors are strategically interdependent, each actor’s preferences over her available actions depend on her expectations about the actions the other actors will take. Thus strategic interdependence applies only in the presence of a very specific kind of uncertainty: each actor must be uncertain about what the other actors will do. Thus, each actor can, at best, choose her actions on the basis of expectations about how the other actors will behave. In an interaction that entails strategic interdependence, none of the actors involved get to know what the other actors will do before choosing their own actions.

For instance, in the model above of the interaction between the organizer and the regime leader, the regime leader must give an order to her thugs about how they should respond to any protest that occurs before the organizer chooses whether to protest. Thus, she must make her decision on the basis of nothing more than an expectation about whether the organizer will protest. In contrast, if the regime leader could simply wait, and then give orders only if a protest occurs, her decision would be much simpler!

For this reason, when we model political interactions that may entail strategic interdependence, we are always think very carefully about the timing of the involved actors’ actions. If one actor will choose an action before another actor, and the latter actor will see the action chosen by the former actor before choosing her own action, the latter actor will not have to make a choice under uncertainty about the former actor’s choice. Thus she need not base her choice on expectations about what her counterpart will do!

Pause and complete check of understanding 1 now!

Game-Theoretic Models

As might be a apparent from the COU you just completed, interactions that entail strategic interdependence can be difficult to describe, explain and analyze using words alone. After all, persons in these actions are interdependent. So it is difficult to describe aspects of any one person’s expectations, preferences or actions without having to refer to the expectations, preferences and actions of other persons in the group. And of course, the expectations, preferences and actions of each one of those other persons in turn depend on the expectations, preference and actions of the others! So things get messy in a hurry.

PPT therefore uses a category of models called game-theoretic models to depict and explore political interactions that entail strategic interdependence. Game-theoretic models describe only the features of an interaction that induce strategic interdependence, and by doing so help us to isolate the role each of those features might play in shaping the expectations and incentives of the persons involved.

There are a variety of different kinds of game-theoretic models. In this lesson, we’ll focus exclusively on models called simultaneous-move games. “Simultaneous-move” means that these models depict persons who all must choose their actions at a single moment in time. Thus, no person knows for sure at the time he chooses his action what actions the other persons will take. Thus, simultaneous-move game-theoretic models straightforwardly depict the uncertainty inherent in strategic interdependence – i.e. each person much choose her action without knowing what actions the other persons will take. Thus each person can, at best, choose between her actions on the basis of expectations about what the other persons will do.

We’ll illustrate the elements of a simultaneous move game by building one to depict the interaction between the organizer and regime leader discussed in the previous section. Recall that the organizer chooses whether to protest or to not protest. The regime leader chooses whether to order her security services to respond to any protest with overwhelming violence or to order her security services to respond to any protest with limited violence. The organizer and regime leader are strategically interdependent because each of their preferences over their available actions depend on their expectations about the action of their counterpart as follows:

| Organizer’s Expectations about Regime’s Response to Protest | Organizer’s Preferences |

|---|---|

| Overwhelming violence | Organizer prefers to not protest instead of protest |

| Limited violence | Organizer prefers to protest instead of not protest |

| Regime Leader’s Expectation about the Organizer’s Action | Regime Leaders’s Preferences |

|---|---|

| Will stage a protest | Leader prefers to order limited violence instead of overwhelming violence |

| Will not stage a protest | Leader prefers to order overwhelming violence instead of limited violence |

Every simultaneous-move game starts by specifying a set of persons and for each person a set of available actions. Thus we’ll specify these elements as follows:

- Set of Persons:

- Organizer

- Regime leader

- Sets of Available Actions:

- For the organizer:

- Protest

- Do not protest

- For the regime leader:

- Order services to respond to any protest with overwhelming violence

- Order services to respond to any protest with limited violence

- For the organizer:

As may be apparent from the above, the persons and sets of available actions in a simultaneous move game are almost self-explanatory. The third element of a simultaneous move game, in contrast, – i.e. the payoff function – takes a bit of work to describe.

The payoff function is the most important element of a simultaneous move game, since it is the core tool for depicting strategic interdependence. To construct and understand a payoff function, you first need to grasp two prior concepts: a profile of actions and the set of all profiles of actions.

For instance, in the simultaneous move game we began to construct above, the sets of available actions are:

Sets of Available Actions:

- For the organizer:

- Protest

- Do not protest

- For the regime leader:

- Order services to respond to any protest with overwhelming violence

- Order services to respond to any protest with limited violence

One profile of actions in this game, then, is: \left( \text{Protest}, \text{Order services to respond to any protest with limited violence} \right) Notice that this list has one action from each of the two persons’ sets available actions. Specifically, the action “Protest” is from the organizer’s set of possible actions and the action “Order services to respond to any protest with limited violence” is from the regime leader’s set of possible actions.

The set of all profiles of actions is exactly what it sounds like: It amounts to the list of every possible profile of actions. For instance, recall again that the sets of available actions in the simultaneous move game depicting the interaction between the organizer and the regime leader is:

Sets of Available Actions:

- For the organizer:

- Protest

- Do not protest

- For the regime leader:

- Order services to respond to any protest with overwhelming violence

- Order services to respond to any protest with limited violence

Thus the set of all profiles of actions is: \left\{ \begin{array}{l} \left( \text{protest}, \text{overwhelming} \right),\\ \left( \text{protest}, \text{limited} \right),\\ \left( \text{no protest}, \text{overwhelming} \right),\\ \left( \text{no protest}, \text{limited} \right),\\ \end{array} \right\} where we’ve abbreviated “order services to respond to any protest with overwhelming violence” as “overwhelming” and “order services to respond to any protest with limited violence” as “limited”.

With these two concepts in hand, we can now define a payoff function.

To see what a payoff function is and what it accomplishes, recall that when persons are strategically interdependent, each person’s preferences over their available actions depend on their expectations about the actions the other persons will take. For instance, the organizer’s and regime leader’s preferences over their actions depend on their expectations about the actions of their counterparts as follows:

| Organizer’s Expectations about Regime’s Response to Protest | Organizer’s Preferences |

|---|---|

| Overwhelming violence | Organizer prefers to not protest instead of protest |

| Limited violence | Organizer prefers to protest instead of not protest |

| Regime Leader’s Expectation about the Organizer’s Action | Regime Leaders’s Preferences |

|---|---|

| Will stage a protest | Leader prefers to order limited violence instead of overwhelming violence |

| Will not stage a protest | Leader prefers to order overwhelming violence instead of limited violence |

A payoff function assigns utility levels to each person at each profile of actions in order to represent exactly this sort of dependence of preferences on expectations. For instance, suppose we assign utility levels the profiles (\text{protest}, \text{overwhelming}) and (\text{protest}, \text{limited}): as follows:

| Profile of Actions | Organizer’s Utility Level | Regime Leader’s Utility Level |

|---|---|---|

| (\text{protest}, \text{overwhelming}) | -1 | -2 |

| (\text{protest}, \text{limited}) | 1 | -1 |

Notice how this depicts the idea that if the leader expects the organizer to protest, then the leader prefers to order the security services to respond to any protest with limited instead of overwhelming violence. It does this by raising the leader’s utility level from -2 to -1 when her action changes from “order overwhelming violence” to “order limited violence” and the organizer protests. By assigning a higher utility level to the leader at (\text{protest}, \text{limited}) than at (\text{protest}, \text{overwhelming}), these payoffs depict the idea that if the organizer protests then the leader will end up better off if he has ordered limited violence than if he has ordered overwhelming violence.

Of course, the above table assigns utility levels to each of the two persons in the model only for two of the four profiles of available actions. By definition, a payoff function assigns utility levels to the persons in the model at each of profiles of available actions. Thus, in the model we are constructing here, the payoff function will be described by a table with four rows, like this:

| Profile of Actions | Organizer’s Utility Level | Regime Leader’s Utility Level |

|---|---|---|

| (\text{protest}, \text{overwhelming}) | ||

| (\text{protest}, \text{limited}) | ||

| (\text{no protest}, \text{overwhelming}) | ||

| (\text{no protest}, \text{limited}) |

Let’s set the utility levels in this payoff function in a way that represents the strategic interdependence between the organizer and the regime leader. Start with the regime leader. We first want to represent the idea that the regime leader prefers to order the security services to respond to any protest with limited violence instead of overwhelming violence if she expects protest to occur. Thus we’ll assign a higher utility level for the regime leader at (\text{protest}, \text{limited}) than at (\text{protest}, \text{overwhelming}) like so:

| Profile of Actions | Organizer’s Utility Level | Regime Leader’s Utility Level |

|---|---|---|

| (\text{protest}, \text{overwhelming}) | -2 | |

| (\text{protest}, \text{limited}) | -1 | |

| (\text{no protest}, \text{overwhelming}) | ||

| (\text{no protest}, \text{limited}) |

On the other hand, we want to represent the idea that the regime leader prefers to order the security services to respond to any protest with overwhelming violence instead of limited violence if she expects no protest to occur. Thus we’ll assign a higher utility level for the regime leader at (\text{no protest}, \text{overwhelming}) than at (\text{no protest}, \text{limited}), like so:

| Profile of Actions | Organizer’s Utility Level | Regime Leader’s Utility Level |

|---|---|---|

| (\text{protest}, \text{overwhelming}) | -2 | |

| (\text{protest}, \text{limited}) | -1 | |

| (\text{no protest}, \text{overwhelming}) | 1 | |

| (\text{no protest}, \text{limited}) | 0 |

Now consider the utility levels for the organizer. First we want to represent the idea that the organizer prefers to protest instead of to not protest if he expects the leader to order limited violence. Thus we’ll assign a higher utility level for the organizer at (\text{protest},\text{limited}) than at (\text{no protest},\text{limited}), like so:

| Profile of Actions | Organizer’s Utility Level | Regime Leader’s Utility Level |

|---|---|---|

| (\text{protest}, \text{overwhelming}) | -2 | |

| (\text{protest}, \text{limited}) | 1 | -1 |

| (\text{no protest}, \text{overwhelming}) | 1 | |

| (\text{no protest}, \text{limited}) | 0 | 0 |

Second we want to represent the idea that the organizer prefers to not protest instead of protest if he expects the leader to order overwhelming violence. Thus we’ll assign a higher utility level for the organizer at (\text{no protest},\text{overwhelming}) than at (\text{protest},\text{overwhelming}), like so:

| Profile of Actions | Organizer’s Utility Level | Regime Leader’s Utility Level |

|---|---|---|

| (\text{protest}, \text{overwhelming}) | -1 | -2 |

| (\text{protest}, \text{limited}) | 1 | -1 |

| (\text{no protest}, \text{overwhelming}) | 0 | 1 |

| (\text{no protest}, \text{limited}) | 0 | 0 |

Since the above table lists all the profiles of actions, it amounts to a fully-specified payoff function. Thus we have a complete simultaneous move game depicting the interaction between the organizer and regime leader:

There is one more important point to note about simultaneous move games before you practice constructing one in the upcoming COUs. When assigning utility levels for the game above, we only considered each person’s preference ordering over her available actions for whatever expectation she might have about the action of her counterpart. For instance, we noted that the organizer prefers to protest instead of to not protest when she expects the regime leader to order limited violence, and thus we set the protest organizer’s utility level at the profile (\text{protest}, \text{limited}) to 1 and the protest organizer’s utility level at the profile (\text{no protest}, \text{limited}) to 0.

However, unlike in many other kinds of PPT models, in game-theoretic models, the difference between the utility levels matters in addition to the order of utility levels. Moreover, the size and direction of change in a person’s utility level when we vary her expectations but hold her action constant can also have a meaningful interpretation. So, for instance, this payoff function, even though it assigns the same ordering to the utility levels as the one above, has very different implications:

| Profile of Available Actions | Organizer’s Utility Level | Regime Leader’s Utility Level |

|---|---|---|

| (\text{protest}, \text{overwhelming}) | 0 | 0 |

| (\text{protest}, \text{limited}) | 1 | 10 |

| (\text{no protest}, \text{overwhelming}) | 10 | 1 |

| (\text{no protest}, \text{limited}) | 0 | 0 |

You’ll learn why these differences matter later in the lesson. For now, all you need to know is that both the order and the sizes of the differences between utility levels in a payoff function matter!

Pause and complete check of understanding 2 now!

Pause and complete check of understanding 3 now!

Pause and complete check of understanding 4 now!

2-By-2 Games

It may be evident from the COUs you just worked through that small changes to a game-theoretic model can substantially increase the model’s complexity. Specifically, if we increase the number of persons a model depicts, or increase the number of actions from which each person chooses, we can end up with a game-theoretic model that is too complicated to be of much use.

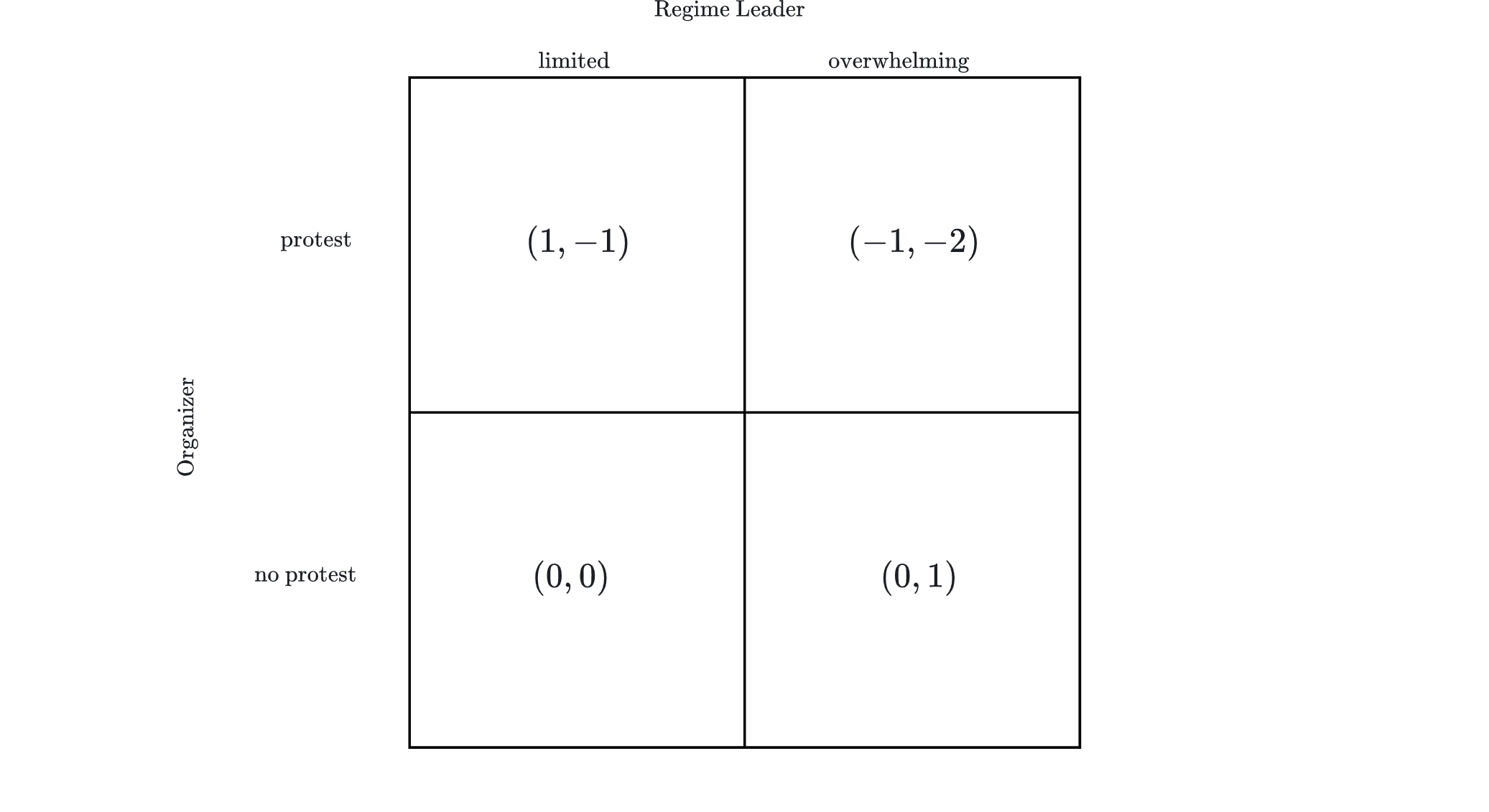

For this reason, a critical tool for modeling strategic interdependence in PPT is the 2-by-2 game. A 2-by-2 game is the simplest possible kind of game-theoretic model. It depicts just two persons who each choose between just two actions. For instance, here again is the game-theoretic model we constructed to depict the interaction between a resistance organizer and the leader of a repressive regime:

This is a “2-by-2 game” because it depicts two persons – the organizer and the regime leader – who each choose between two actions – protest or not protest for the organizer and order limited violence or order overwhelming violence for the regime leader.

Matrix Form

2-by-2 games are typically written using a convention called matrix form. Take any 2-by-2 game. The matrix form of that game amounts to a table (or, to use the more math-y terminology, a “matrix”) with two rows and two columns, like so:

The table’s two columns represent the two actions available to one of two persons, while the rows represent the two actions available to the other persons. For instance, one matrix form of the 2-by-2 game between the organizer and the regime leader would be:

It does not matter which person’s actions are represented by the rows and which person’s actions are represented by the columns. Thus another matrix form of the 2-by-2 game between the organizer and the regime leader is this:

It also does not matter how we order either persons’s actions. For instance, both of the following are valid matrix forms of the 2-by-2 game between the organizer and the regime leader:

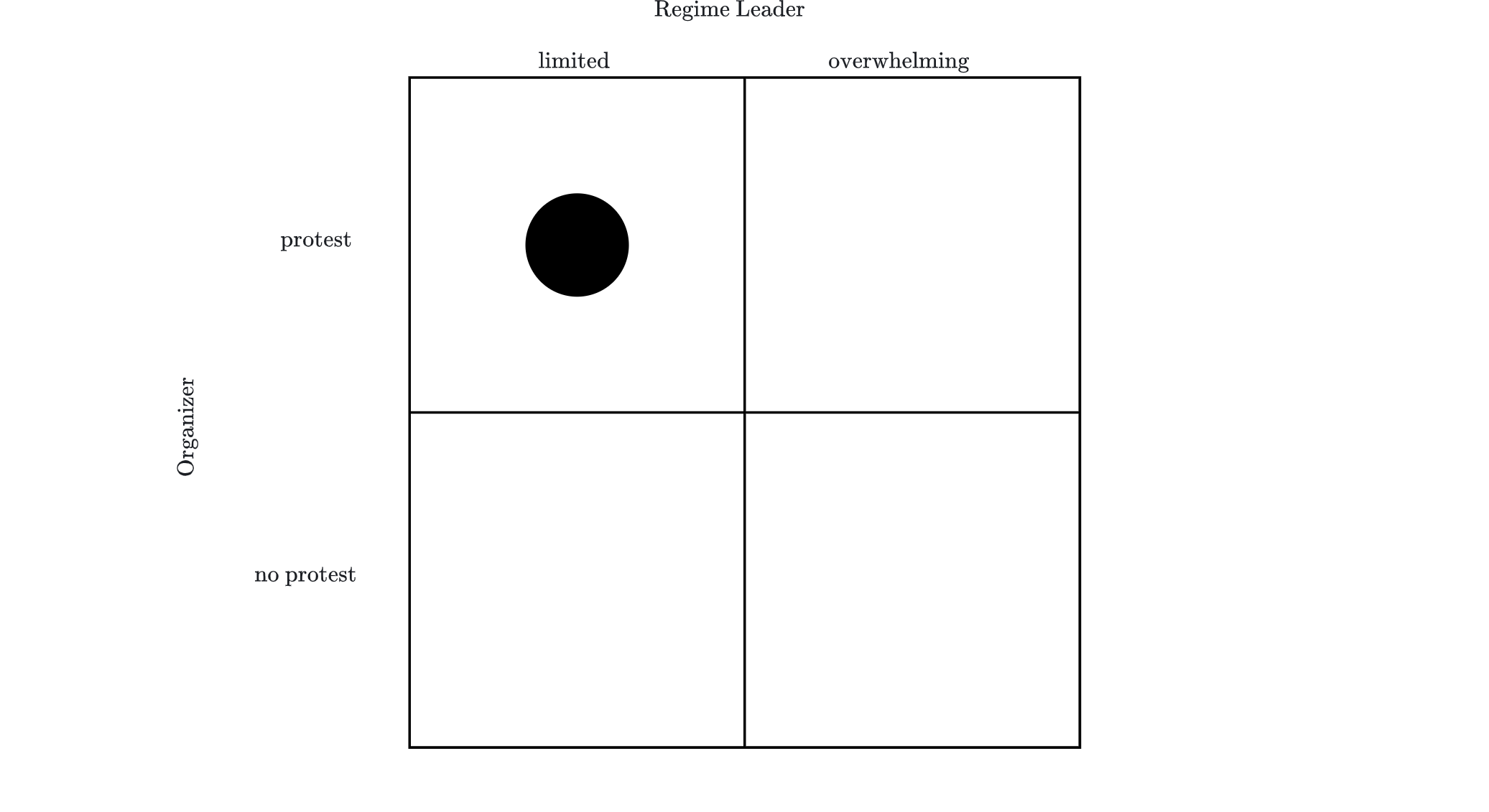

The cells of the table (or matrix) in the matrix form of a 2-by-2 game are used to represent the game’s payoff function. To understand how this works, notice that each cell in the matrix form corresponds to one of the profiles of actions. For instance, in the matrix form below, the cell containing the large black dot corresponds to the profile of actions in which the organizer protests and the regime leader orders her security services to respond to any protest with limited violence:

So, we can depict the game’s payoff function by writing each person’s utility level at each profile in the appropriate cell. For instance, here again is the payoff function we used to construct the game between the organizer and regime leader:

| Profile of Actions | Organizer’s Utility Level | Regime Leader’s Utility Level |

|---|---|---|

| (\text{protest}, \text{overwhelming}) | -1 | -2 |

| (\text{protest}, \text{limited}) | 1 | -1 |

| (\text{no protest}, \text{overwhelming}) | 0 | 1 |

| (\text{no protest}, \text{limited}) | 0 | 0 |

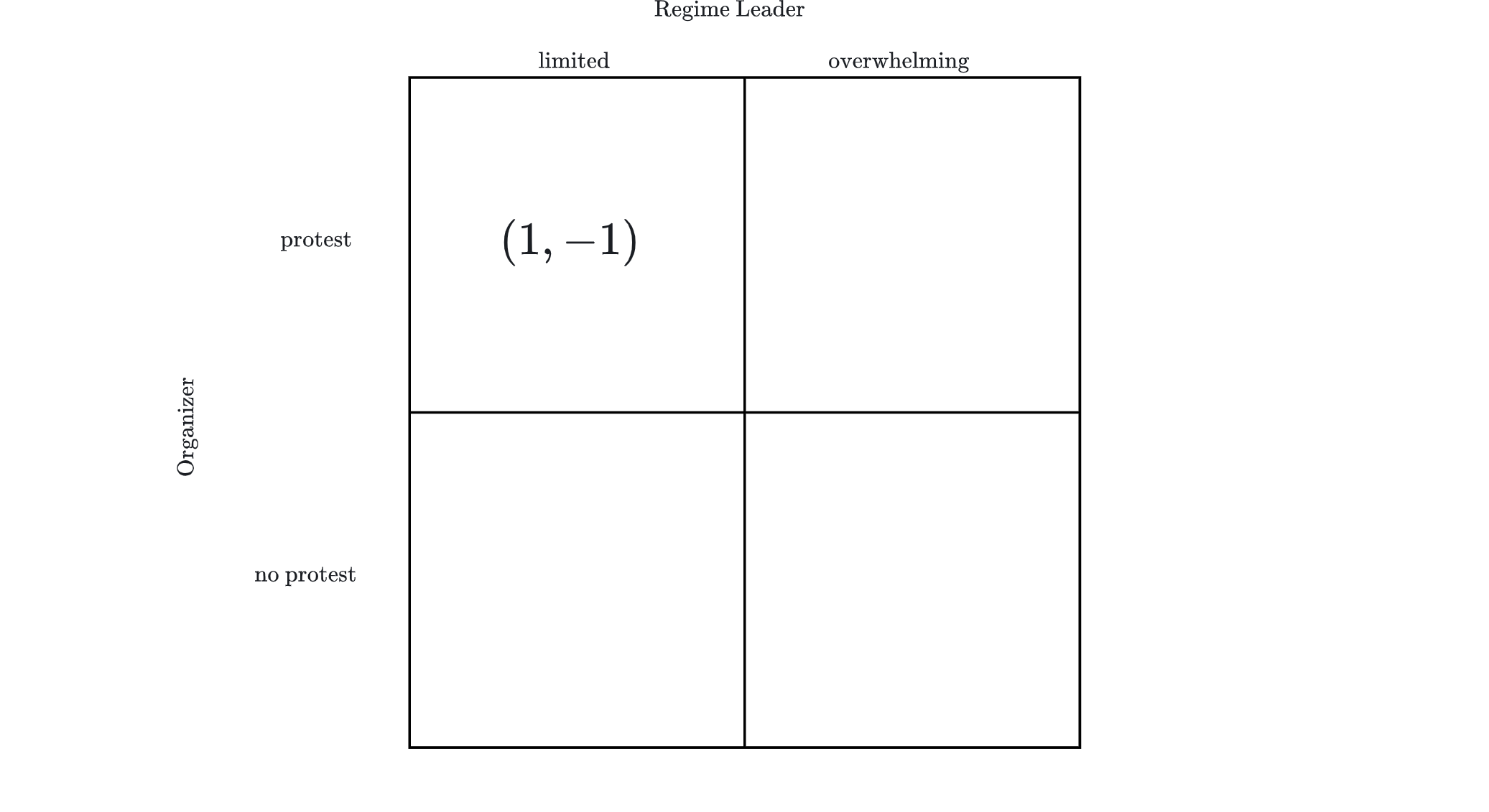

At the profile (\text{protest},\text{limited}), this payoff function assigns utility level 1 to the organizer and utility level -1 to the regime leader. So to capture these utility levels in the matrix form, we would write (1,-1) in the top-left cell of the above table like so:

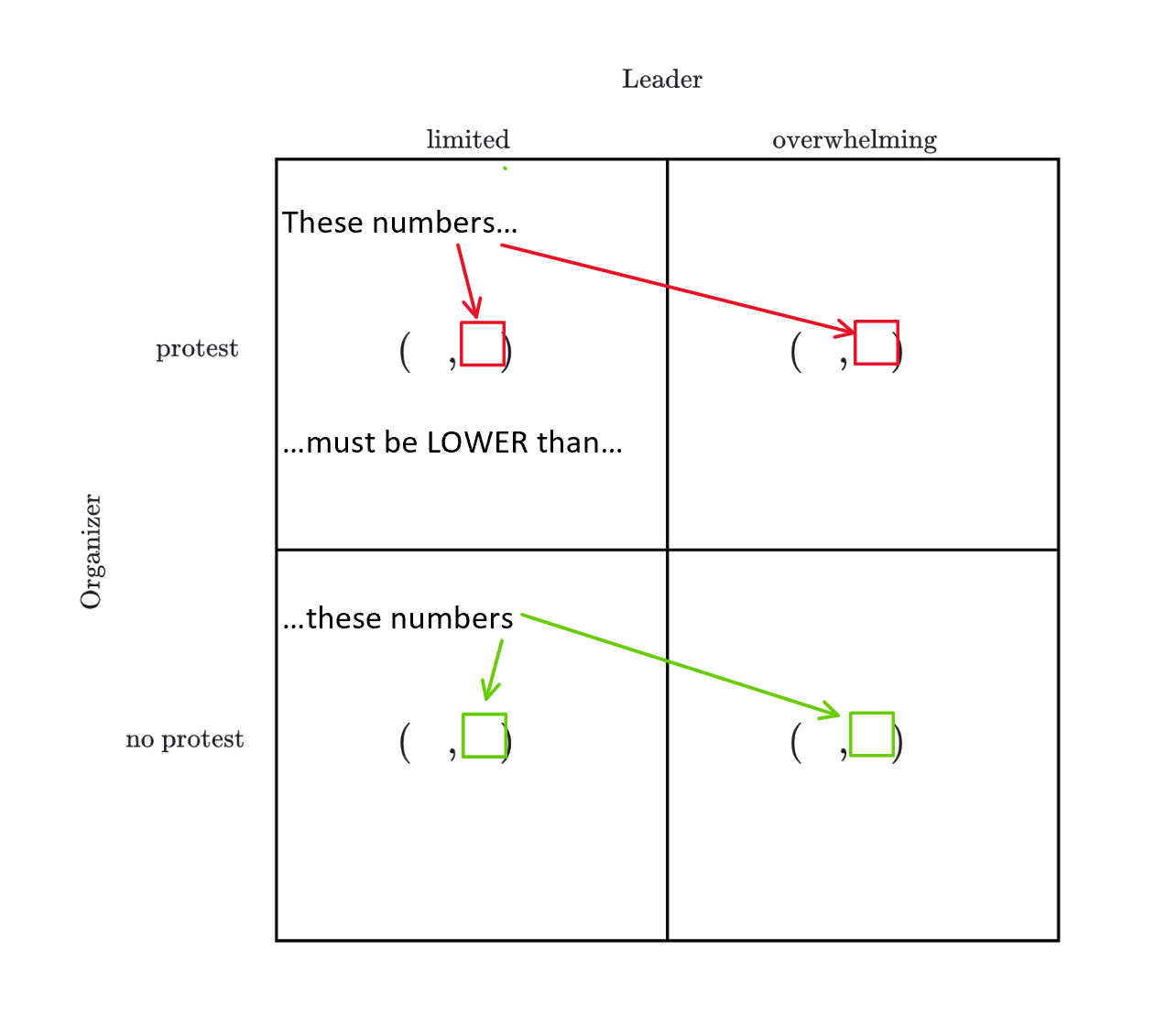

This brings us to the one aspect of the matrix form that takes some practice to master and that, for better or worse, you must master in order to effectively use the matrix form: When we write the utility levels assigned to the persons at the profile in a given cell, we always write the row-person’s utility level first and the column-person’s utility level second.

To see how this convention applies, look once again at the payoff function for the game between the organizer and the regime leader:

| Profile of Actions | Organizer’s Utility Level | Regime Leader’s Utility Level |

|---|---|---|

| (\text{protest}, \text{overwhelming}) | -1 | -2 |

| (\text{protest}, \text{limited}) | 1 | -1 |

| (\text{no protest}, \text{overwhelming}) | 0 | 1 |

| (\text{no protest}, \text{limited}) | 0 | 0 |

Now suppose that we want to write this game in a matrix form in which the organizer is the “row-person” and the regime leader is the “column person”, like so:

Since the organizer is the row-person and the regime leader is the column-person in this matrix form, the Utility Level Ordering Convention requires that in each cell, we write the organizer’s utility level from the profile corresponding to that cell first and the regime leader’s utility level from the profile corresponding to that cell second. Thus, applying the payoff function as written in the table above, the matrix form is:

Pause and complete check of understanding 5 now!

Expectations Matter

Now that you have a handle on the matrix form of 2-by-2 games, we can use it to illuminate what might be the most important insights about strategic interdependence in politics that game-theoretic models produce. To develop these insights, we’ll start by constructing the matrix form of a 2-by-2 game introduced earlier in this lesson in which an organizer chooses whether or not to stage a protest while a regime leader chooses whether to order her security services to respond to any protest with limited violence or to respond to any protest with overwhelming violence:

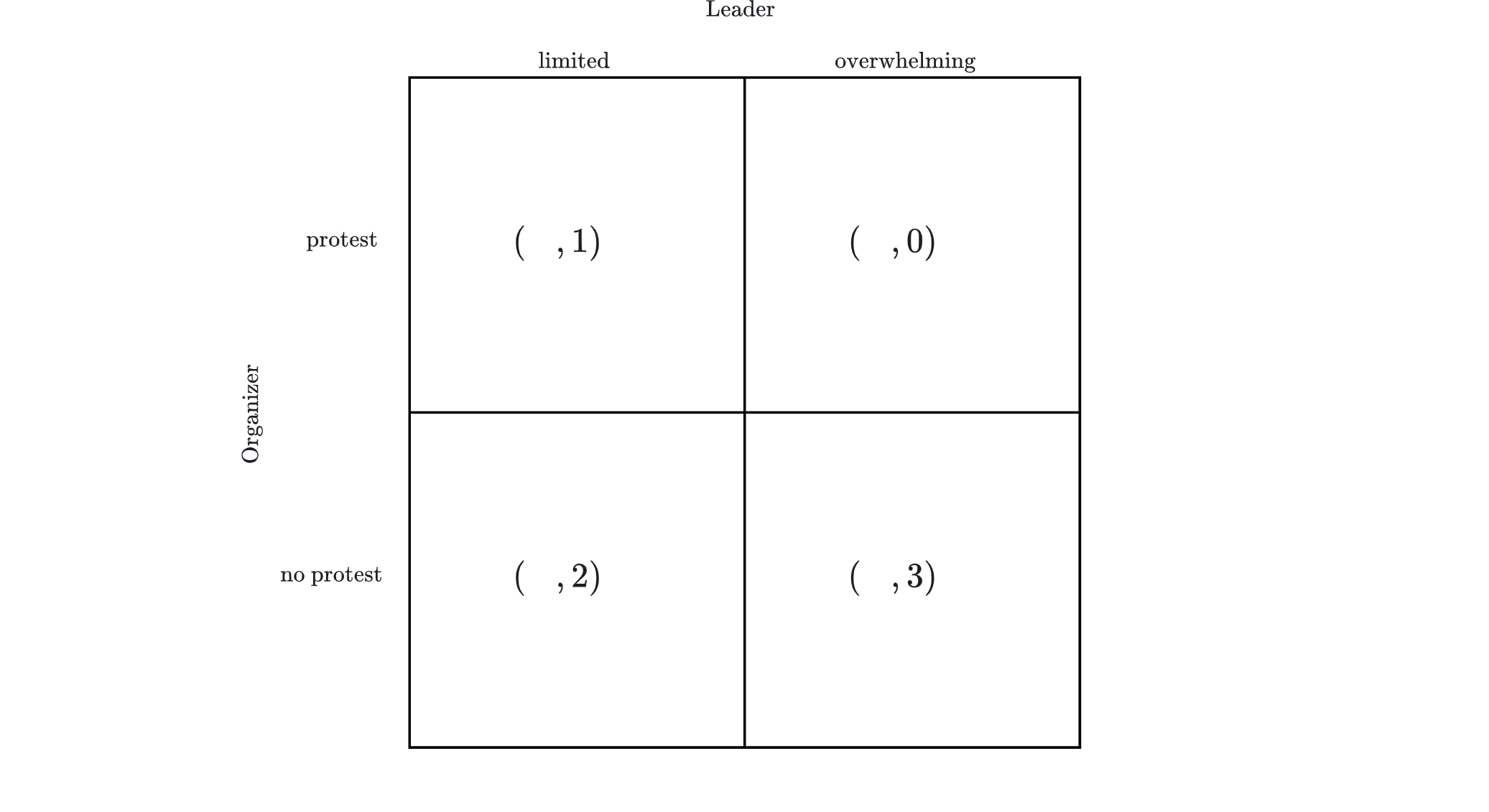

We’ll begin by assigning utility levels to the regime leader in a way that depicts an important regularity in the relationships between repressive regimes and the populations they rule. Because the thugs these regimes use to carry out repressive violence are vastly outnumbered by the populations they rule, sufficiently large street protests can undermine the fear that keeps the population quiescent and compliant. Thus mass street protests are always threatening to a repressive regime’s hold on power regardless of how the regime responds to them. In short, from the point of view of a repressive regime’s leaders and supporters, protests are always worse than no protests.

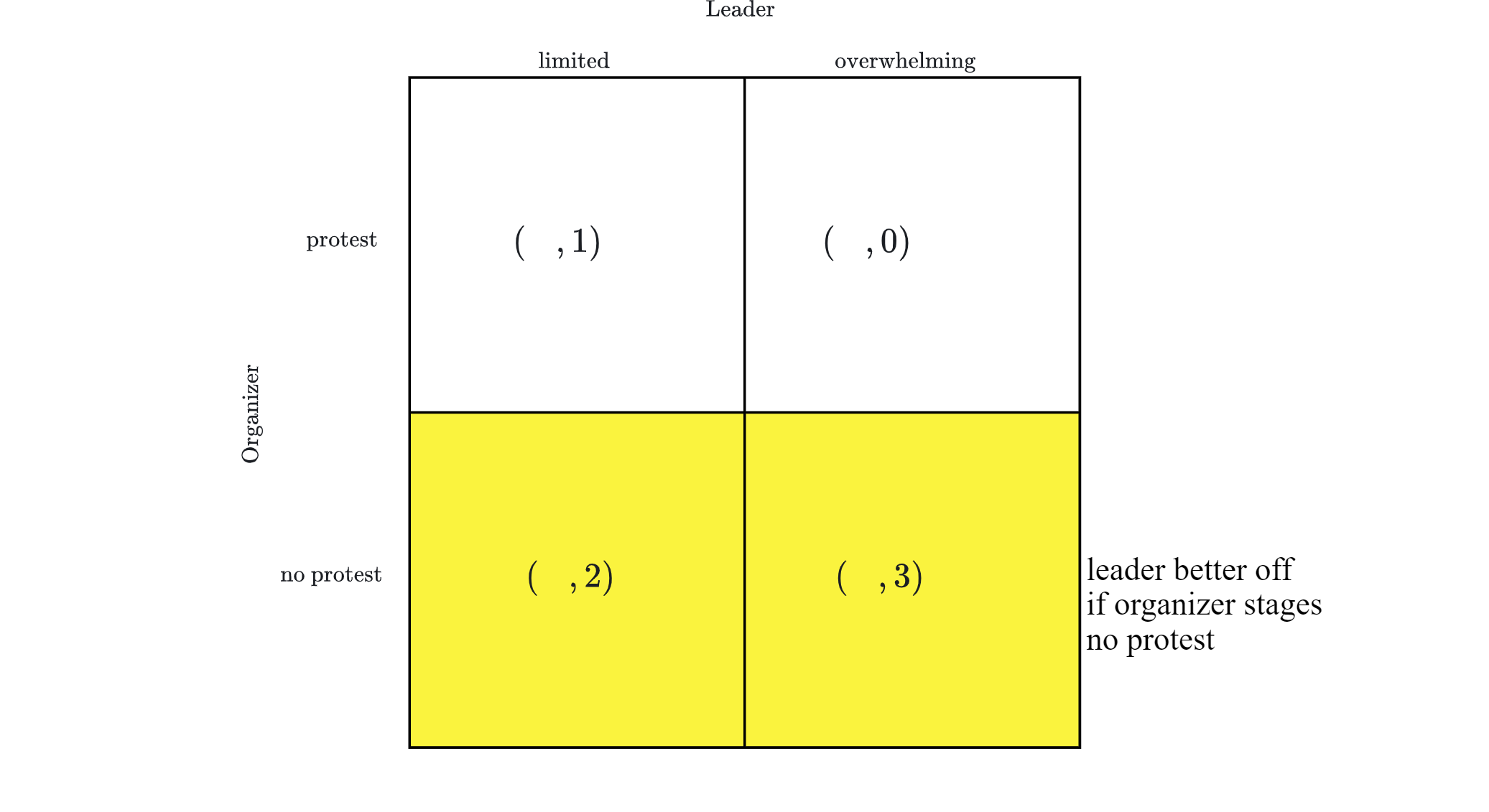

To explore the implications of this regularity, we’ll assign utility levels to the regime leader that are lower if the organizer stages a protest than if the organizer stages no protest regardless of the leader’s actions. In the matrix form we wrote above, the top row represents outcomes that occur when the organizer stages a protest and the bottom row represents outcomes that occur when the organizer stages no protest. Thus we’ll assign payoffs to the regime leader in the top row that are lower than those assigned in the bottom row, like so:

At the same time, we will continue to depict the organizer and leader as strategically interdependent. More specifically, we’ll depict the regime leader as preferring to order limited instead of overwhelming violence if she expects protest and preferring to order overwhelming instead of limited violence if she expects no protest. This means that the leader’s utility level must be higher in the top-left cell than in the top-right cell, and higher in the bottom-right cell than in the bottom-left cell. Thus, applying the Utility Level Ordering Convention for the matrix form, the following utility levels assigned for the regime leader satisfy our requirements:

Notice that dependence of the leader’s preferences over the actions she takes does not affect the fact that she is better off if no protest occurs. Regardless of what she does, she is better off if the organizer does not stage a protest. Thus we mark the matrix to indicate this as follows:

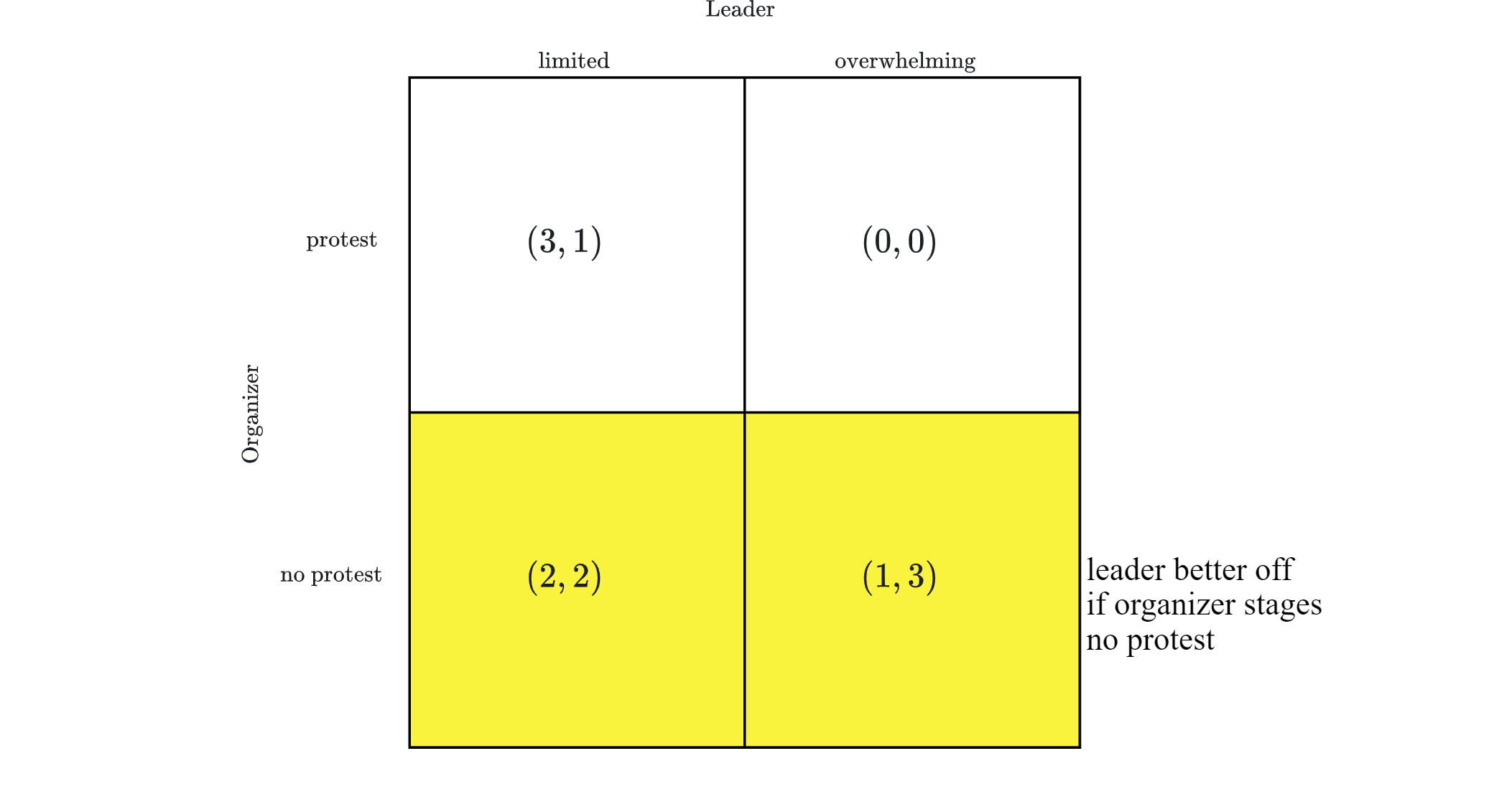

So under what conditions will the organizer not stage a protest? Make two assumptions about the organizer. First, assume that regardless of what action she takes, she is better off if the leader orders her thugs to respond to any protest with limited instead of overwhelming violence. Presumably, the organizer simply prefers to live under a regime that behaves with less brutality, regardless of what she does. Second, assume that a protest that is met with overwhelming violence with strengthen the regime and a protest that is met with limited violence will weaken the regime. Thus the organizer prefers to not stage instead of to stage a protest if she expects the leader to order overwhelming violence, and prefers to stage instead of to not stage a protest if she expects the leader to order limited violence. We’ll depict these assumptions by assigning payoffs for the organizer as follows:

Under these assumptions, the model generates a subtle but powerful insight regarding strategic interdependence: Because the leader and organizer are strategically interdependent, each one of them’s inclination to choose one action or another depends on her expectations about the action her counterpart will choose. Put more simply, each actor’s behavior depends on her expectations. With this in mind, think of the interaction depicted in the model from the point of view of the regime leader: The leader will be better off if the organizer does not stage a protest. What might cause the organizer to do that? Well, whether the organizer is inclined to stage protest depends on her expectations about what the leader will do. Specifically, she will be inclined to stage a protest if she expects the leader to order limited violence and not inclined to stage a protest if she expects the leader to order overwhelming violence. So, since the leader is better off if the organizer stages no protest, the leader has an incentive to influence the organizer’s expectations. More precisely, the leader will be better off if the organizer expects the leader to order overwhelming violence, because then the organizer will be less inclined to stage a protest. Conversely, the leader will be worse off if the organizer expects the leader to order limited violence, because then the organizer will be more inclined to stage a protest.

More generally:

This insight can substantially enrich one’s understanding of the behavior of political actors who are strategically interdependent. It suggests that the significance of political actors’ choices often lies in the effects of those choices on other persons’ expectations about future behavior.

For instance, consider again Sam Block’s protest actions in August of 1962. What were their aims and impacts? Recall that these actions involved tiny numbers of persons. In each one, Block lead just a few other black residents of Greenwood to the courthouse to openly and publicly defy the regime’s demands of black deference to whites. And recall that these actions entailed severe personal risk for Block and his colleagues. Each of them knew they had a chance of being killed and even tortured to death for their defiance. What could such tiny protests produce that would make those risks worthwhile?

Block was strategically interdependent with the leaders of the white supremacist regime and the thugs that enforced the regime’s demands. The effects of his actions on his goals depended on how the thugs responded. Overwhelming violence in response to Block’s early protests may well have terrified the local population, ruling out mass participation in any further protest. Limited violence, on the other hand, could be expected to have the opposite effect. Moreover, as potential participants in resistance against the regime, black residents of Greenwood were strategically interdependent on one another. They knew they had power in numbers. Thus if many of them joined the resistance all at once, they would protect each other from retaliation and perhaps weaken the regime’s hold on power. If instead only a few joined, those few would surely be punished and the regime would be strengthened.

Because of these interdependencies, each actors expectations about what the other actors would do were critical to the choices they made. Block’s early protest actions, for instance, were in effect a bet on how the regime would respond. He expected to be physically attacked for his provocations. And for him, that was the point. A physical attack that did not kill him would amount (and did amount, in the event) to an opportunity to prove his physical courage to black residents of Greenwood. This, he hoped, would change their expectations about how many of their fellow residents might join the resistance, and thus change their expectations about the risks and prospects they would assume by getting involved themselves.

Pause and complete check of understanding 6 now!

Pause and complete check of understanding 7 now!

References

Footnotes

Fortunately, Block was not murdered or lynched. After several of his visits to the courthouse, however, he was evicted by his landlord, jumped and beaten by a small band of white terrorists, and a few days after that narrowly escaped a lynch mob by jumping out of a second story window just as organizers of the mob were running up a set of stairs to grab him. (Payne 2007, 150–51)↩︎

To be clear, a mob was organized to lynch Block in response to his protests. But Block successfully escaped the mob and so the lynching that was apparently intended by the regime did not occur.↩︎