COU 3: Modeling Subjective Beliefs

The Puzzle of War

“The central puzzle about war,” writes James Fearon, (Fearon 1995) “is that wars are costly but nonetheless war recurs.” How, Fearon asks, can “rational leaders who consider the risks and costs of war…end up fighting nonetheless”? In this COU you’ll learn about part of Fearon’s argument – one of the most influential arguments in the study of war – by using probabilistic models of uncertainty to depict subjective beliefs. Work through the following partial account of Fearon’s thinking, responding to the prompts along the way.

We can illustrate the puzzle Fearon points out with a simple model of war:

Imagine a piece of territory that the leaders of two neighboring nations both wish to control. For instance, you can think of the eastern regions of Ukraine that were invaded and occupied by Russian armed forces and mercenaries in 2014, or the region of Jammu and Kashmir that spans the disputed border between India and Pakistan.

If the two neighboring states go to war over this territory, the eventual outcome – once one of the two sides has been defeated or once hostilities have ended in a negotiated peace – will be some division of the territory between the two states. To depict this, draw a line representing the total land area of the disputed territory:

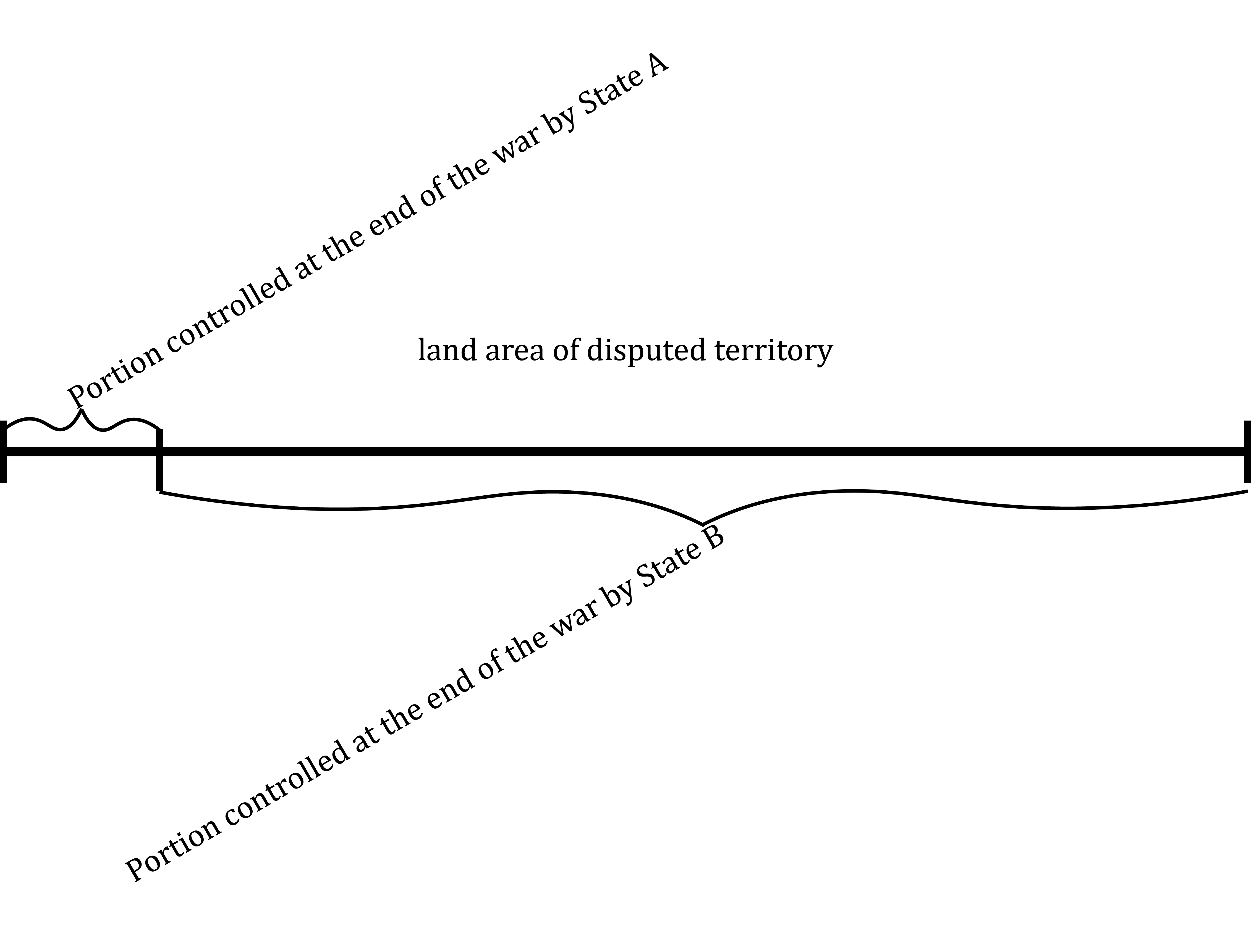

Then note that we can depict the portion of the disputed territory controlled by each of the two nations – call them “Nation A” and “Nation B” – once the war has concluded by dividing the line like so:

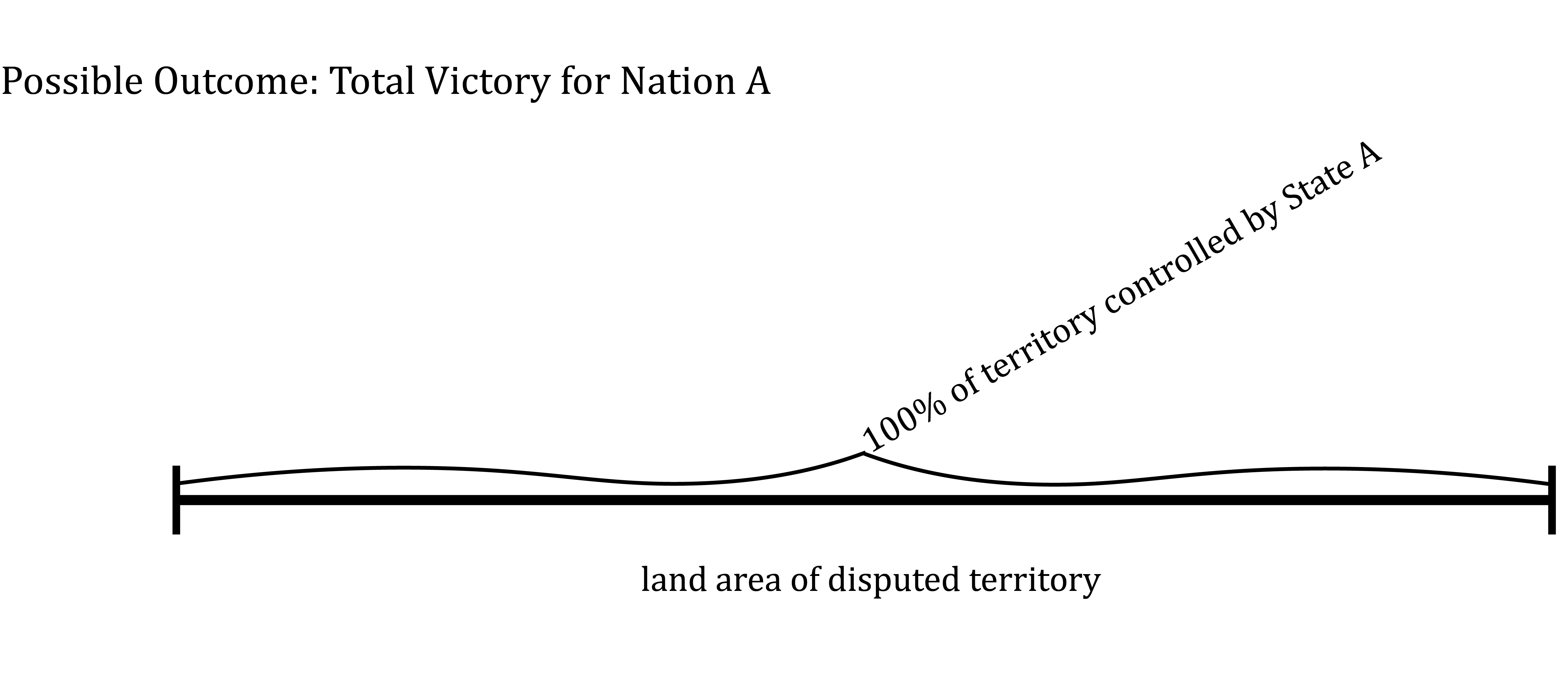

With this way of thinking about the end of any war in hand, shift to imagining a moment before any war begins. Imagine a leader of Nation A thinking prospectively about what will happen if a war ensues between nations A and B. Presumably, Nation A’s leader has beliefs about the division of the territory in which a war will culminate. For instance, perhaps she believes that three outcomes of a war are possible. First, a war could result in total victory for Nation A, like this:

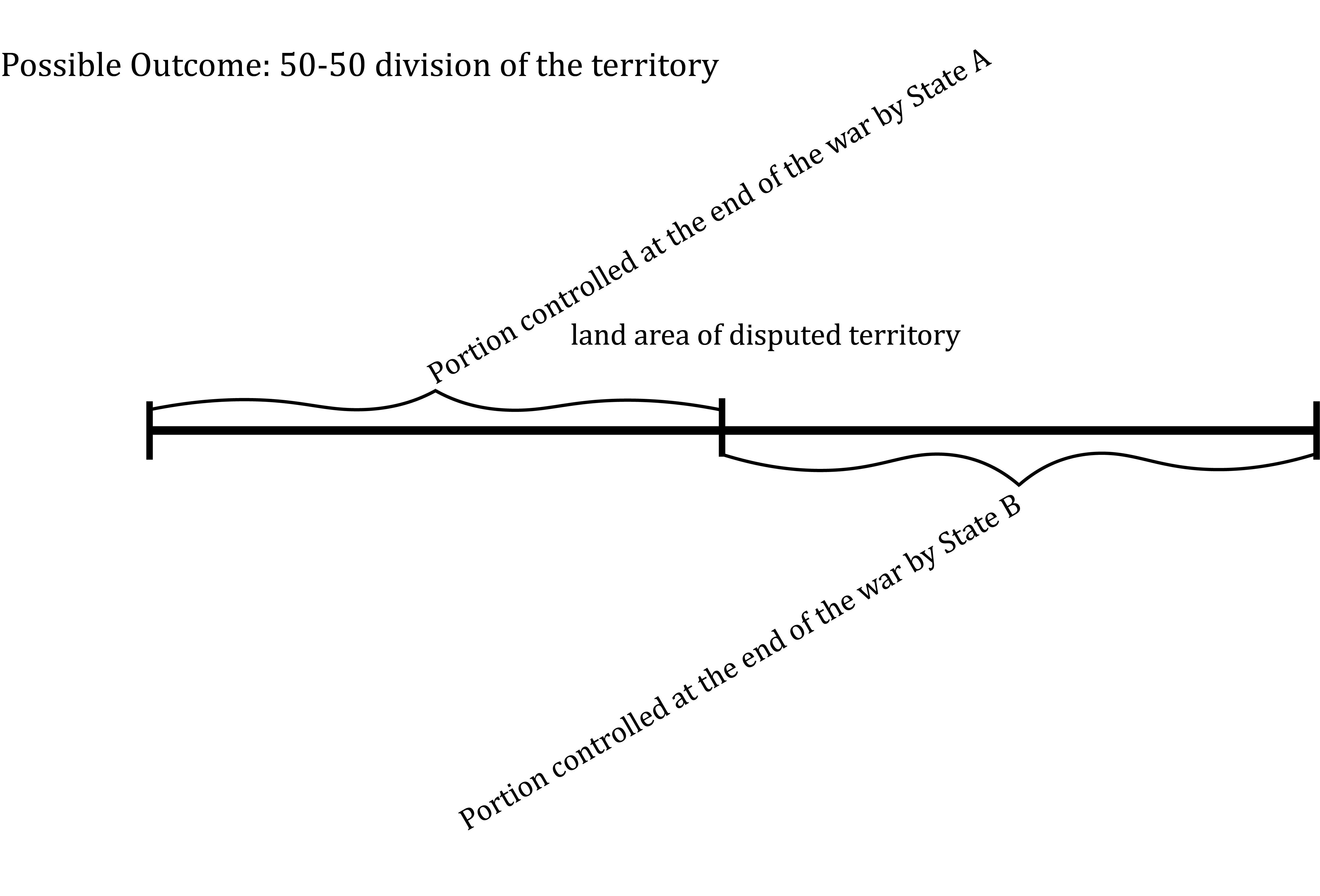

Second, a war could result in a 50-50 division of the territory, like this:

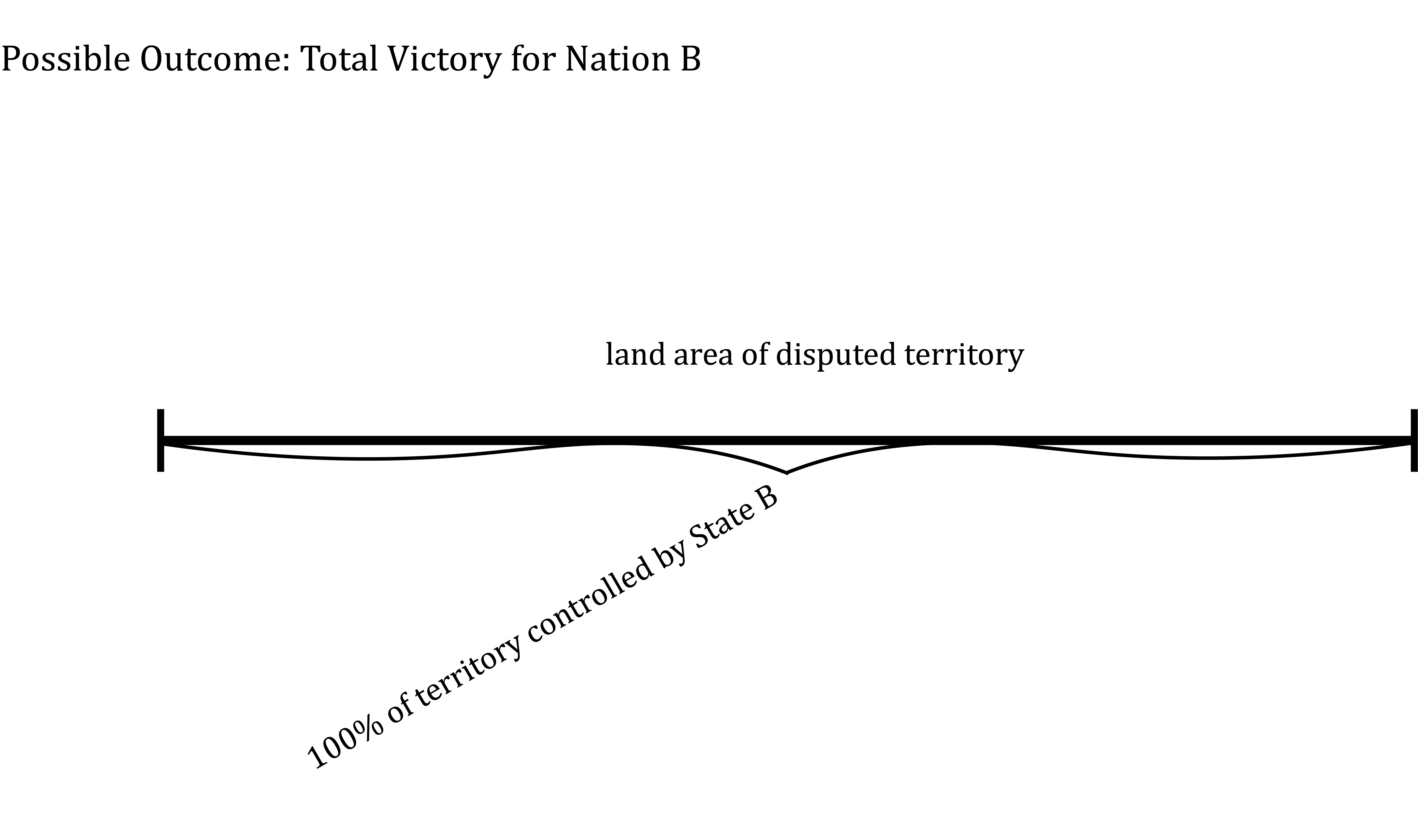

Third, a war could result in total victory for Nation B, like this:

Now imagine that a leader of Nation A – call her “Leader A” – and a leader of Nation B – call him “Leader B” – have the same beliefs about how the disputed territory will end up divided between the two nations if they go to war. For instance, perhaps Leader A and Leader B believe that if the two nations go to war, total victory for Nation A and total victory for Nation B are equally likely, but a 50-50 division of the territory is far more likely than total victory by one side or the other.

Imagine these two leaders meet to negotiate a settlement between the two nations that they hope will avert a war. Imagine that Leader A says to Leader B:

Look, my friend, we both know what will happen if our nations go to war. There is a small chance that one of us will win the entirety of the disputed territory. But it’s far more likely that we will each end up with half of it. Either way, thousands of civilians and soldiers on both sides will be killed and wounded, and cities in both of our nations will suffer terribly from arial bombardments. Surely, then, we can agree now to a peace treaty that divides territory outright, half of it for each of our nations. This is where we are most likely to end up anyway. And by agreeing to those terms now, we arrive at that result without paying the terrible costs a war will impose on each of our nations.

Part of the “central puzzle of war”, according to Fearon, is how wars ever occur, given that negotiated settlement like the one imagined above are possible. After all, note Leader A’s irrefutable logic: Both sides understand what will result from a war. And they can arrive at that result through a negotiated peace without paying the terrible costs a war inevitably imposes on all parties.

So, a story about how wars occur when leaders of the combatant nations are rational must somehow resolve this puzzle. What prevents leaders from coming to negotiated settlements that avoid the costs of war and are thus better for both sides than what they know war will yield?

Fearon’s study amounts to an inventory of processes through which rational leaders, despite mutually recognizing that any division of spoils arrived at through negotiations is better for both sides than the same division arrived at through war, might nonetheless end up at war. One of these is “disagreements about relative power”. Perhaps leaders’ subjective beliefs about the relative likelihoods of different outcomes of a war diverge, and this makes a negotiated settlement impossible.

For instance, suppose Leader A thinks that total victory for Nation A is overwhelmingly likely in the event of a war, while Leader B thinks that total victory for Nation B is overwhelmingly likely event of a war. Given Leader A’s beliefs, she would presumably only accept a negotiated settlement in which the vast majority of the disputed territory were allocated to Nation A. Leader B, on the other hand, would only accept the opposite. Thus there is no settlement that the parties mutually prefer to war, and war ensues.

It may seem clear that war will result if the leaders of two nations have radically different beliefs about their nations’ relative military strength, and thus are both mutually (over)optimistic that a war will lead to total victory for their nation. But how, Fearon asks, “could rationally led states have conflicting expectations about the likely outcome of military conflict?” Part of the answer may lie in states’ military secrecy. Nations often try to keep details about their militaries’ size, technology, organization, and tactics secret. Thus each nation’s leaders’ beliefs about the relative strength of their military will be based in part on information to which other nations’ leaders have limited access. Thus, to the extent that nations successfully hide their strengths, it’s quite possible for beliefs about the relative likelihoods of the possible outcomes of a conflict to diverge. This may be one reason why nations that are officially enemies in fact regularly share information about their military capacity and operations! Perhaps they believe that nations that mutually agree on their relative military strength are less likely to go to war.

Rubric

Prompt 1

You earn 2 points if you respond with a valid probabilistic model that represents the uncertainty about which of three outcomes will occur: “total victory for nation A”, “a 50-50 division of the territory”, “total victory for nation B”. You earn 0 points otherwise.

Prompt 2

You earn 2 points if you respond with two valid and identical probability distributions that both (a) represent uncertainty over the outcomes “total victory for nation A”, “a 50-50 division of the territory”, “total victory for nation B” and (b) assign probabilities so that “total victory for nation A” and “total victory for nation B” are equally likely and “a 50-50 division of the territory” is 20 times more likely than total victory by either A or B.

You earn 1 point if you respond with two valid and identical probability distributions that both represent uncertainty over the outcomes “total victory for nation A”, “a 50-50 division of the territory”, “total victory for nation B”, but that do not assign probabilities so that “total victory for nation A” and “total victory for nation B” are equally likely and “a 50-50 division of the territory” is 20 times more likely than total victory by either A or B.

You earn 0 points otherwise.

Prompt 3

You earn 2 points if you respond with two valid probability distributions that both (a) represent uncertainty over the outcomes “total victory for nation A”, “a 50-50 division of the territory”, “total victory for nation B” and (b) assign probabilities just as required in the prompt (i.e. Leader A believes “total victor for nation A” is overwhelmingly likely, etc.)

You earn 1 point if you respond with two valid probability distributions that both represent uncertainty over the outcomes “total victory for nation A”, “a 50-50 division of the territory”, “total victory for nation B”, but that do not assign probabilities that represent relative likelihoods for each of the two distributions as described in the prompt.

You earn 0 points otherwise.